Gluck to Gorecki

A small and highly subjective selection of some the most beautiful, dramatic, ‘difficult’ and significant ‘classical’ composers and compositions from the last 400 years.

A small and highly subjective selection of some the most beautiful, dramatic, ‘difficult’ and significant ‘classical’ composers and compositions from the last 400 years.

I have had a passing interest in what is often and erroneously termed ‘classical’ music since the early 80s, but it was only during the past 18 months since working on my M R James project of orchestrated ‘extended songs’ and ‘A Grimm Little Fantasy For Orchestra’, that I have more seriously and extensively explored ‘classical music’ for pleasure and to learn how to compose in that genre.

Most of these names and pieces will be familiar to anyone with even a passing interest in this music, but hopefully you will still find something new that you’ll like.

I’ve chosen recent HD performances where possible in preference to older recordings which reveal more texture in the music and I also selected clips where the piece has been featured in a film so that it is given some context (the Handel aria featured in the film ‘Farinelli’, for example, offers a glimpse of the baroque world that Handel inhabited). Feel free to share or recommend this list and links with others who you think might like it. P

EARLY MUSIC

MEDIEVAL (c.5th-15th century)

Plainsong (unaccompanied church music sung in unison in medieval modes and in free rhythm corresponding to the accentuation of the words, which are taken from the liturgy.)

Gregorian chant a single vocal line in free rhythm

RENASSAINCE (c.1300-1700)

Thomas Tallis 16thc English composer and master of early Choral Music

‘Spem in Alium’

BAROQUE (c.1600-1750)

Gluck ‘Orphee et Eurydice’ (starts at 4:16)

Purcell ‘Dido’s Lament’ (starts at 0:59)

I have a particular fondness for Baroque instrumental music and opera. ‘Dido’s Lament’ (also known as ‘When I Am Laid In Earth’ from his opera ‘Dido and Aeneas’, is very well known and turns up on those specious and rather condescending ‘classic FM’ charts that make me squirm, but if you like this I can heartily recommend similarly elegant and stately work by Lully, Rameau, Monteverdi and Handel, although the latter’s extremely elongated and repetitive vocal lines are an acquired taste.

Handel’s aria ‘Lascia Chio Pianga’ from his opera ‘Rinaldo’ featured in a clip from the film ‘Farinelli’ (1994) about the life of the celebrated 18th century castrato singer.

J S Bach 1685-1750 (not to be confused with his less celebrated son C P E Bach) Beethoven was among many who considered Bach THE greatest composer of them all. Every serious composer without exception has studied and learnt from him.

J S Bach 1685-1750 (not to be confused with his less celebrated son C P E Bach) Beethoven was among many who considered Bach THE greatest composer of them all. Every serious composer without exception has studied and learnt from him.

If you find his choral work too heavy and his organ pieces not to your liking then the best place to start is with his piano music especially ‘The Well-Tempered Clavier’ and ‘The Art of Fugue’ which will dazzle with their intricacies and wealth of rich harmonies under virtually every leading note. I warmly recommend the young French virtuosi David Fray’s ‘Fray Plays J S Bach -A film by Bruno Monsaigneon’ and while I am praising Fray, his ‘Fray Plays Mozart’ is also a delight. It shows him in rehearsal with a very bemused ensemble of professionals who don’t know whether to take his remarks seriously or not, but Fray’s insights into the music really add to one’s understanding of the pieces he plays.

Philippe Jaroussky – a young counter tenor who specialises in beautiful highly ornate baroque opera. There are several productions and recitals featuring Jaroussky that I would recommend for those wishing to sample several baroque composers and the highly decorative art of the period ‘La Voix des Reves’ being one. This clip is from a different concert. Starts at 1:33

CLASSICAL PERIOD (c.1730-1820)

Haydn (‘the father of the symphony’)

Some might find Haydn and Mozart a mite ‘prissy’ (formal) for their liking but I discovered a new aspect to Haydn when I heard his string quartets

I also found Mozart’s darker and more dramatic side (as heard here in the final scene of ‘Don Giovanni’) more appealing than his sprightly courtly instrumental music and his profound insights into the human condition in ‘Le Nozze di Figaro’ and ‘Cosi Fan Tutte’) overcame any reservations and preconceptions/misconceptions that I had previously entertained. Put aside any memories you might have taken from the film ‘Amadeus’ which portrays Mozart as a crude buffoon and sample scenes from The Royal Opera’s 2006 production of ‘Figaro’ (under the baton of Pappano) and its 2008 staging of ‘Don Giovanni’ (under Mackerras) to see and hear Mozart’s finest operas as they should be experienced. This clip is from a different production but there appears to be no clip of the stagings I have recommended on YouTube at present in sufficiently high quality.

Early Beethoven Symphony 3rd (Eroica) second movement ‘Funeral March’ starts at 20:17 Beethoven was a very different character in terms of both temperament and working method to Mozart. While Mozart appears to have virtually channelled his music onto the page with little revision, Beethoven laboured for months, even years developing his major works from very small fragments. I must confess that I find the symphonies less appealing primarily because they are so familiar and most of his orchestral music too ‘German’ for my taste (though brilliant of course) whereas the intimate chamber music – particularly the Piano sonatas and string quartets are a source of infinite pleasure and riches.

Brahms symphony no 4

Brahms symphony no 4

I have worked and studied with classical musicians and composers who are casually dismissive of Brahms but I suspect that attitude is a form of academic conceit. I even met one who dismissed Mozart as someone who “reworked the same basic ideas over and over” and was of the opinion that Mozart “only wrote 4 operas worthy of their place in the repertoire”! But that attitude is indicative I think of those at work in orchestral music today who feel that melody is something to be avoided as ‘populist’ and that the more abstract the piece, the more worthy it is of attention. I have to say, that once composition becomes a matter of intellect -akin to a mathematical process – rather than the expression of emotion and the heart, it leaves me cold. Or as Benjamin Britten once said, “seeking after a new language appears to have become more important than saying what you mean…if we rejected the past we would just be making funny noises.”

I can’t imagine an ‘academic’ composer writing this – can you?

ROMANTIC PERIOD 19thc

Middle period Beethoven Fifth Piano Concerto

Late Beethoven ‘the difficult’ late string quartets

(when told by a frustrated musician that these were “impossible to play” he replied that they were intended “for a later age”)

Chopin

You will also hear Chopin featured in Roman Polanski’s Academy Award winning film ‘The Pianist’ (2002)

Schubert ‘Death and the Maiden’ string quartet

Perhaps the most accessible string quartet ever written, certainly the best known and loved though I personally have a particular fondness for the Haydn quartets and all of the Beethoven.

Tchaikovsky Russian symphonist, ballet and opera composer– too sugary and overly ‘emotional’ for my liking though I have been known to melt during ‘The Dying Swan’.

Verdi – together with Puccini, Verdi is arguably the most popular composer of 19thc Italian opera – very dramatic and tuneful ‘Caro Nome’ is from ‘Rigoletto’, one of my favourite operas and the first I listened to seriously. This is my favourite aria from it (a highlight among many) starts at 1:10:00

I had assumed that his predecessor Rossini (composer of ‘William Tell’ and ‘The Barber of Seville’) would be too ‘silly’ for my taste but I was happily mistaken. Here is his opera buffo (comic opera) ‘Le Comte D’Ory’. Another with the same tenor lead (Juan Diego Florez) and this marvellous comic soprano Natallie Desay is ‘Le Fille Du Regiment’

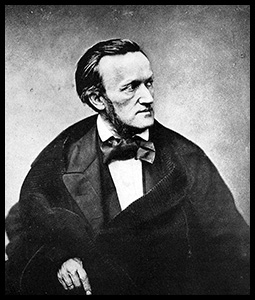

Wagner ‘Siegfried’s Funeral March’ from ‘Gotterdammerung’, the fourth opera in The ‘Ring’.

Wagner ‘Siegfried’s Funeral March’ from ‘Gotterdammerung’, the fourth opera in The ‘Ring’.

It took me several years and repeated efforts to enter Wagner’s sound world and the intimidatingly monumental epic that is ‘The Ring’, but once I found a way in (listening to a short passage from various productions until it became familiar) I was hooked. The only Wagner opera that I can’t listen to is ‘Renzi’, his first because it doesn’t sound like him, but rather more like Meyerbeer, who he was attempting to imitate. Wagner bridges what is commonly and erroneously referred to as ‘classical music’ and early 20thc orchestral music. His journey away from tonal music in ‘Tristan Und Isolde’ with the famous ‘Tristan chord’ encouraged others to explore music that veered away from the comfort of ‘home’ keys. Here is the beginning of ‘modern’ music growing out from a single ‘dissonant’ chord

Wagner Pilgrim’s Chorus from ‘Tannhauser’

I don’t have a problem separating Wagner the man and his odious racist ‘philosophy’ from his sublime music. I think of composition as originating from the Higher Self - as an inspired idea which is largely but not entirely untainted by the individual who then crafts it and makes it presentable. Having said that, if a particular composer is associated with a malevolent regime as Wagner was with the Nazis, then surely no one has the right to impose that on a people traumatised by the Holocaust as Barenboim attempted to do in Israel some years ago. As much as I admire Barenboim as a musician, surely if it distresses people then their opposition should be respected and any thought of ‘freedom of expression’ has to be set aside.

Mahler Late 19thc Austro-German late-romantic composer-conductor who often juxtaposed the ‘serious’ and the ‘banal’ to explore his own psychological state and the contradictory nature of the emerging century than any symphonist before him, while expanding the scope and size of the symphony. His ‘Adagio’ from the 4th Symphony was used in Visconti’s arthouse film ‘Death In Venice’ which led to it becoming the only piece by Mahler that the non classical music lover might be familiar with.

One of my favourite composers whose work rewards repeated listening and whose life needs to be understood to fully appreciate his music. I’ve read several biographies and critical works in recent months and watched several documentaries of which this is one of the best and most illuminating.

Richard Strauss (‘the Mozart of the 20thc’) Not to be confused with Johann Strauss the composer of saccharine sweet Viennese waltzes! Richard Strauss bridged the 19thc and the dissonant early 20thc with his early operas ‘Salome’ and ‘Elektra’ and symphonic tone poems, of which ‘Also Sprach Zarathrustra’ is the best known (from its use as the main theme in Stanley Kubrick’s film ‘2001’)

Richard Strauss (‘the Mozart of the 20thc’) Not to be confused with Johann Strauss the composer of saccharine sweet Viennese waltzes! Richard Strauss bridged the 19thc and the dissonant early 20thc with his early operas ‘Salome’ and ‘Elektra’ and symphonic tone poems, of which ‘Also Sprach Zarathrustra’ is the best known (from its use as the main theme in Stanley Kubrick’s film ‘2001’)

The early operas are more ‘difficult’ to get to grips with, but are worth persevering with. It is hard to believe that the same man wrote the perennially popular ‘Rosenkavalier’, a retro-opera (or archaic pastiche, if you prefer). I hated ‘Salome’ when I first heard it, but knowing that it was a pivotal work I persevered and eventually ‘got it’ after listening to the first ten minutes of several productions until I could identify key themes. This is a curious looking production, with costumes that might have been borrowed from the original TV series of ‘Star Trek’ but musically it was the one which I found most accessible. ‘Salome‘

Stravinsky ‘Rite of Spring’. Conductor Michael Tilson Thomas is one of those ‘popular educators’ who are able to reveal the methods of composition by performing a musical autopsy and analysis of a specific piece without patronising the musically uneducated (for which I have been grateful on more than one occasion!). His lecture/performance series ‘Keeping Score’ is a must see. This is the ‘Rite of Spring’ episode

Another great educator was the late conductor/composer Leonard Bernstein whose enthusiasm for the music he loves is infectious (Here he is on Mahler)

British conductor Simon Rattle is another. (Rattle’s documentary series on ground breaking 20th orchestral music, ‘Leaving Home’, is essential viewing)

Carl Orff ‘Carmina Burana’ 20thc composer who used a bawdy 13thc medieval text to compose one of the most powerful works of the interwar period (1935-6). Here it is featured in John Boorman’s film ‘Excalibur’.

Nationalist Composers (very much of their country)

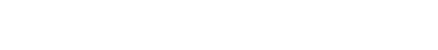

Shostakovich 20thc Russian composer not ‘difficult’ to listen to at all but nevertheless intellectually stimulating without being contrived or self-consciously clever-another of my favourite composers.

Shostakovich 20thc Russian composer not ‘difficult’ to listen to at all but nevertheless intellectually stimulating without being contrived or self-consciously clever-another of my favourite composers.

Sibelius - Finish composer – ‘Finlandia’ a symphonic tone poem (written 1900)

Dvorak – Symphony 9 ‘From The New World’

19thc Czech composer who went to America where he incorporated Negro spirituals and folk music into what became his most popular symphony

Rachmaninov – another ‘typical’ Russian – his piano concertos which I love are full of lush romantic sweeping melodies

Samuel Barber ‘Adagio’ . Although Barber could not be described as a major composer, the use of this piece in the film ‘Platoon’ and many other movies has made it very familiar and much loved.

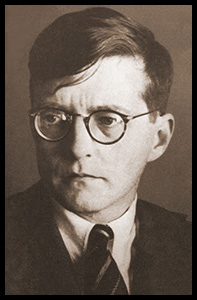

Vaughan Williams 20thc English orchestral composer. His ‘Variations on a theme by Thomas Tallis’ is characteristic of English pastoral music (cleverly using the ‘tune’ of a 16thc composer Tallis in a 20th c idiom)

Vaughan Williams 20thc English orchestral composer. His ‘Variations on a theme by Thomas Tallis’ is characteristic of English pastoral music (cleverly using the ‘tune’ of a 16thc composer Tallis in a 20th c idiom)

Although he is not strictly a pastoral composer as his other symphonies reveal. If you like this you might also like Elgar, the entirely self-taught ‘amateur’ composer and conductor whose music evokes the lost idyll of Edwardian England. This recording of the Cello Concerto features the internationally celebrated cellist Yo Yo Ma who I was privileged to interview many years ago - a very warm and genuine person whose generosity and depth of feeling can be heard in his playing.

Benjamin Britten (the only significant British opera composer since Purcell 400 years earlier – quite ‘difficult’ to like!). He ingeniously juxtaposes the text of the Latin requiem mass with the First World War poems of Wilfred Owen in his ‘War Requiem’

Ligeti (very difficult Hungarian avant-garde composer who composed in microtones – the notes between the notes ie only those that can NOT be played on a fretted instrument or piano. Most famous for his ethereal vocal piece used in Kubrick’s film ‘2001’

Minimalism – Philip Glass (begun using only electronic instruments then went into orchestration, opera, chamber music etc using same repeated phrases overlaid with counter melodies, rhythms) very easy to like if you don’t mind mind-numbing repetition!

Michael Nyman – my favourite contemporary composer because he blended Purcell (another of my favourite composers) with 20th century minimalism but only on one album/film soundtrack ‘The Draughtman’s Contract’ a wilfully abstruse ‘highbrow’ murder mystery set in the 18th century!

Michael Nyman – my favourite contemporary composer because he blended Purcell (another of my favourite composers) with 20th century minimalism but only on one album/film soundtrack ‘The Draughtman’s Contract’ a wilfully abstruse ‘highbrow’ murder mystery set in the 18th century!

I still regret having declined Nyman’s offer to orchestrate and record one of my songs back in the mid 80s when he was working with Kate Bush, but I was terrified that he might not like my music and that would have affected the way I heard his own music. Sometimes I could kick my younger self!

Other contemporary composers who are worth investigating include the late John Tavener (‘spiritual/esoteric’), American minimalist John Adams and British composer Harrison Birtwistle (who I would categorize as extremely unmelodic and difficult to listen to, though it is for that reason that I am repeatedly drawn to his opera The Minotaur as I am to Britten. The more unapproachable the composer, the more I try to understand and appreciate their music. Though I can’t imagine myself ever making a serious effort to grasp Stockhausen or John Cage, but please don’t let me put you off doing so)

Henryk Gorecki – easy to like best-selling contemporary Polish classicist. His ‘Symphony of Sorrowful Songs’ is a moving tribute to those murdered by the Nazis and one of the most accessible though untypical contemporary works which has been described as ‘sacred minimalist’.

If you liked that you might also find the music of Estonian Arvo Part appealing.

And with that I leave you to explore further the infinite world of classical/orchestral music.

-Paul.

Some kind people call me ‘the godfather of steampunk’ and ‘the Edgar Allen Poe of Psych-Pop’, so with those strong literary influences it was perhaps inevitable that I would one day ‘grow out of’ the standard 3-minute song format and be looking to develop a more cinematic music with which to set my narrative tales.

Some kind people call me ‘the godfather of steampunk’ and ‘the Edgar Allen Poe of Psych-Pop’, so with those strong literary influences it was perhaps inevitable that I would one day ‘grow out of’ the standard 3-minute song format and be looking to develop a more cinematic music with which to set my narrative tales.

However, I soon discovered that while the themes came readily and so too the countermelodies and harmonies, my rudimentary keyboard technique prevented me from playing more than a few bars at a time. The solution, I discovered, was to copy and paste these short themes or phrases then add to the repeats so that, for example, the opening clarinet line would then be joined by an oboe and low string part in the double basses giving a sinister undertone to the bucolic setting. Something nasty was waiting in the forest. This mixture of intuitive musical exploration, rational narrative thinking and technology helped to bring successive self-contained scenes to life although these were by necessity episodic.

However, I soon discovered that while the themes came readily and so too the countermelodies and harmonies, my rudimentary keyboard technique prevented me from playing more than a few bars at a time. The solution, I discovered, was to copy and paste these short themes or phrases then add to the repeats so that, for example, the opening clarinet line would then be joined by an oboe and low string part in the double basses giving a sinister undertone to the bucolic setting. Something nasty was waiting in the forest. This mixture of intuitive musical exploration, rational narrative thinking and technology helped to bring successive self-contained scenes to life although these were by necessity episodic.